The shoulder is your body’s most mobile joint — and one of the most complex. SIGMA Orthopedics breaks it down simply so you can understand your injury, your surgery, and your recovery pathway.

The shoulder is made of three bones — the humerus (arm bone), scapula (shoulder blade), and clavicle (collarbone). Together, they form three main joints:

The “ball and socket” that powers rotation and lifting.

Connects the clavicle to the acromion.

Anchors the shoulder to your chest.

The labrum is a ring of cartilage that deepens the shoulder socket, keeping it stable during motion.

The capsule and ligaments act like seatbelts — preventing the ball from sliding out of the socket.

Injuries such as SLAP tears or instability occur when these soft tissues stretch or tear.

Knowing your anatomy is the first step toward recovery.

At SIGMA Orthopedics, your care plan goes beyond diagnosis — it’s an engineered journey toward strength, precision, and performance.

Every shoulder patient is enrolled into our 100 Days to Success Program, featuring:

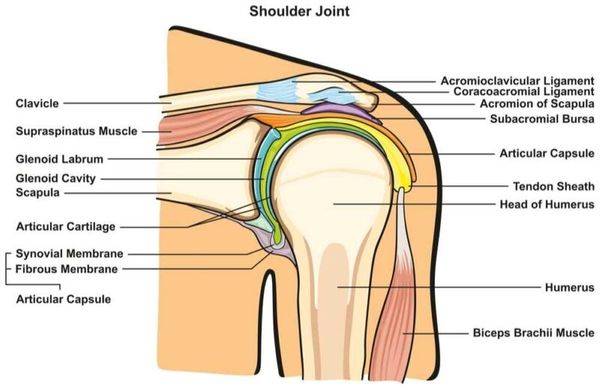

The shoulder joint, also known as the glenohumeral joint, is one of the most complex and mobile joints in the human body. This comprehensive overview details the key anatomical structures and their functional relationships.

Bones and Joints:

The shoulder complex consists of three main bones: the clavicle (collarbone), scapula (shoulder blade), and humerus (upper arm bone). These bones form four joints: the glenohumeral joint, acromioclavicular joint, sternoclavicular joint, and scapulothoracic joint. The glenohumeral joint, a ball-and-socket joint, is formed by the articulation between the humeral head and the glenoid fossa of the scapula.

Joint Capsule and Ligaments:

The glenohumeral joint capsule is reinforced by several ligaments. The superior, middle, and inferior glenohumeral ligaments provide stability. The coracohumeral ligament extends from the coracoid process to the greater tubercle. The coracoacromial ligament forms an arch above the humeral head, protecting it from superior displacement.

Rotator Cuff:

The rotator cuff comprises four muscles and their tendons: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis (SITS). The supraspinatus initiates arm abduction, the infraspinatus and teres minor perform external rotation, and the subscapularis enables internal rotation. These muscles work together to stabilize the humeral head within the glenoid fossa during arm movement.

Additional Musculature:

The deltoid muscle, consisting of anterior, middle, and posterior fibers, is the primary shoulder abductor. The pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, and teres major contribute to internal rotation and adduction. The biceps brachii, particularly its long head, assists in shoulder flexion and stabilization.

Neurovascular Structures:

The shoulder region is innervated by branches of the brachial plexus, including the axillary, suprascapular, and musculocutaneous nerves. The axillary artery and its branches provide blood supply to the shoulder structures. The subacromial bursa, located between the acromion and rotator cuff, facilitates smooth movement of the rotator cuff tendons.

Functional Considerations:

The shoulder complex allows for extensive range of motion in multiple planes: flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, internal and external rotation, and circumduction. This mobility is achieved through the coordinated action of multiple joints and muscle groups, with stability maintained through both dynamic (muscular) and static (ligamentous) mechanisms.

Biomechanical Relationships:

The scapulohumeral rhythm describes the coordinated movement between the scapula and humerus during arm elevation. For every 180 degrees of total arm elevation, approximately 120 degrees occurs at the glenohumeral joint, while 60 degrees results from scapular rotation. This relationship is crucial for maintaining optimal joint function and preventing impingement.

Clinical Significance:

Understanding shoulder anatomy is essential for diagnosing and treating common pathologies such as rotator cuff tears, impingement syndrome, frozen shoulder, and instability. The complex interplay between various anatomical structures means that dysfunction in one area can affect the entire shoulder mechanism.

Anatomical Variations:

Natural variations in glenoid version, acromion morphology, and capsular laxity can influence shoulder function and predisposition to certain pathologies. The size and shape of the acromion, classified into three types, can affect the risk of subacromial impingement.

Developmental Aspects:

The shoulder complex undergoes significant changes during development, with fusion of growth plates and maturation of neuromuscular control. The glenohumeral joint begins as a cartilaginous structure that gradually ossifies, while the rotator cuff develops its characteristic pattern of organization.

This anatomical overview emphasizes the intricate relationships between shoulder structures and their functional significance. The shoulder’s remarkable mobility comes at the cost of potential instability, requiring precise coordination between static and dynamic stabilizers for optimal function.

The shoulder is a complex joint that allows for a wide range of motion, making it crucial in various sports activities. Understanding its intricate anatomy is essential for sports medicine specialists and orthopedic surgeons to effectively diagnose, treat, and rehabilitate shoulder injuries. This report will provide a comprehensive overview of shoulder anatomy from a sports medicine orthopedic perspective.

The shoulder complex consists of three main bones:

• Humerus: The upper arm bone

• Scapula: The shoulder blade

• Clavicle: The collarbone

These bones form three joints:

• Glenohumeral joint: The primary shoulder joint

• Acromioclavicular (AC) joint: Between the acromion of the scapula and the clavicle

• Sternoclavicular (SC) joint: Between the sternum and the clavicle

The glenohumeral joint is a ball-and-socket joint, where the humeral head articulates with the glenoid fossa of the scapula. The glenoid fossa is relatively shallow, contributing to the joint’s instability but allowing for a greater range of motion.

The shoulder joint capsule is a loose, fibrous sac that envelops the glenohumeral joint. It is reinforced by several ligaments:

• Glenohumeral ligaments (superior, middle, and inferior)

• Coracohumeral ligament

• Coracoacromial ligament

These ligaments provide static stability to the joint and prevent excessive translation of the humeral head. In sports involving repetitive overhead motions, these ligaments can become stretched, leading to instability.

The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles and their tendons that surround the glenohumeral joint:

• Supraspinatus: Initiates abduction and stabilizes the humeral head

• Infraspinatus: External rotation and stabilization

• Teres minor: External rotation and stabilization

• Subscapularis: Internal rotation and stabilization

These muscles work together to provide dynamic stability to the shoulder joint and are crucial for controlled arm movements. Rotator cuff tears are common in both contact and overhead sports.

The deltoid is a large, triangular muscle that covers the shoulder joint. It consists of three parts:

• Anterior fibers: Assist in forward flexion and internal rotation

• Middle fibers: Primary abductor of the arm

• Posterior fibers: Assist in extension and external rotation

The deltoid works in conjunction with the rotator cuff to provide power and stability during shoulder movements.

Several other muscles play significant roles in shoulder function:

• Biceps brachii: The long head passes through the bicipital groove and attaches to the superior labrum

• Triceps brachii: Extends the elbow and assists in shoulder extension

• Pectoralis major: Adducts and internally rotates the arm

• Latissimus dorsi: Extends, adducts, and internally rotates the arm

• Trapezius: Elevates and retracts the scapula

• Serratus anterior: Protracts and stabilizes the scapula

These muscles contribute to the overall function and stability of the shoulder complex.

Several bursae surround the shoulder joint, reducing friction between moving structures:

• Subacromial-subdeltoid bursa: The largest and most clinically significant

• Subcoracoid bursa

• Subscapular bursa

Inflammation of these bursae (bursitis) is common in overhead athletes and can contribute to impingement syndrome.

Key neurovascular structures around the shoulder include:

• Axillary nerve: Innervates the deltoid and teres minor muscles

• Musculocutaneous nerve: Innervates the biceps and brachialis muscles

• Suprascapular nerve: Innervates the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles

• Axillary artery and its branches: Provide blood supply to the shoulder region

Understanding the course of these structures is crucial for avoiding iatrogenic injury during surgical procedures.

Although not a true joint, the scapulothoracic articulation is essential for shoulder function. It allows the scapula to glide along the thoracic wall, contributing to the overall range of motion of the upper extremity. Proper scapular positioning and movement (scapulohumeral rhythm) are crucial for optimal shoulder function in sports activities.

The shoulder complex allows for an impressive range of motion:

• Flexion: 0-180 degrees

• Extension: 0-60 degrees

• Abduction: 0-180 degrees

• Adduction: 0-75 degrees

• Internal rotation: 0-70 degrees

• External rotation: 0-90 degrees

This extensive mobility is achieved through the coordinated action of the glenohumeral joint, scapulothoracic articulation, and the AC and SC joints. The concept of force couples, particularly between the rotator cuff and deltoid, is crucial for maintaining joint stability during movement.

Understanding shoulder anatomy is essential for diagnosing and treating common sports-related pathologies:

• Rotator cuff tears: Often seen in overhead athletes and contact sports

• Labral tears: Including SLAP lesions in throwing athletes

• Shoulder instability: Ranging from subluxation to dislocation

• Impingement syndrome: Common in swimmers and tennis players

• AC joint injuries: Frequently seen in contact sports

• Biceps tendinopathy: Often associated with other shoulder pathologies

• Scapular dyskinesis: Can contribute to various shoulder problems

Various imaging modalities are used to evaluate shoulder anatomy and pathology:

• X-rays: Useful for assessing bony structures and alignment

• MRI: Excellent for evaluating soft tissue structures, including the rotator cuff and labrum

• CT: Provides detailed bony anatomy, particularly useful for assessing glenoid bone loss in instability

• Ultrasound: Allows dynamic assessment of the rotator cuff and biceps tendon

Understanding normal shoulder anatomy is crucial for interpreting these imaging studies accurately.

Knowledge of shoulder anatomy is critical for surgical planning and execution. Common approaches include:

• Deltopectoral approach: Used for various shoulder procedures

• Superior approach: Often used for rotator cuff repair

• Posterior approach: Useful for addressing posterior instability or reverse total shoulder arthroplasty

Each approach requires careful consideration of the underlying neurovascular structures and muscle attachments.

It’s important to recognize that anatomical variations exist and can impact clinical presentation and treatment:

• Os acromiale: An unfused acromial ossification center

• Glenoid morphology: Variations in glenoid version and inclination

• Rotator cuff footprint: Variations in the size and shape of tendon insertions

• Biceps tendon insertion: Variations in the attachment to the superior labrum

These variations can influence biomechanics and predispose individuals to certain pathologies.

The shoulder’s complex anatomy allows for remarkable mobility but also predisposes it to various injuries, particularly in the athletic population. A thorough understanding of shoulder anatomy from a sports medicine orthopedic perspective is essential for accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and successful rehabilitation of shoulder injuries. This knowledge forms the foundation for advanced techniques in shoulder arthroscopy, arthroplasty, and other surgical interventions. As our understanding of shoulder biomechanics and pathophysiology continues to evolve, so too will our approaches to managing shoulder disorders in athletes.